This article originally appeared in the Journal of Financial Crime, Volume 4 / Number 1 / Autumn/Fall 2020. By Thomas Bock, global co-head, Financial Crimes Risk Management; and Michelle Goodsir, former managing director.

Anti-money laundering (AML) and anti-bribery and corruption (ABC) programs, by themselves, are important tools in addressing problems that are global in scope. While AML and ABC programs are distinct, they also entail complementary skills, which reflect the nature of the financial crimes they are designed to prevent. Money laundering, bribery and corruption are discrete but related offenses when viewed through a legal lens; they are all forms of financial crime. For this reason, even though AML and ABC programs have historically operated independently, it no longer makes sense to perpetuate that separation. AML and ABC can, and should, collaborate to enhance their effectiveness.

Keeping AML and ABC programs independent tends to obscure holistic views of risk. Widely publicized instances of corruption in recent years show that money laundering is frequently predicated on bribery offenses. The interconnectedness of bribery, corruption and money laundering therefore strongly suggests that institutions adopt a holistic view of risk and a collaborative approach to mitigate financial crimes. Financial regulators and institutions have begun to see further connections from its monitoring capabilities with emerging financial crimes, such as money movements underlying human trafficking and trade in protected animal species. Although convergence of data to support financial crime compliance and respond to these interconnections makes sense, the focus of this article is on the convergence of anti-money laundering and anti-bribery compliance.

Bribery and corruption scandals have been remarkably pervasive, involving government officials and individuals in private-sector entities on nearly every continent.1 Bribery, corruption and money laundering involved in these cases have left a trail of financial losses, litigation, reputational damage, sanctions, government fines and regulatory penalties. A common thread in many of these incidents is organizations’ lack of awareness of what was taking place inside their own operations—a clear sign of silos at work. If ever there were an opportune time for financial institutions to discard the silo approach of yesterday and align and strengthen their AML and ABC programs for today’s environment, now would be the time.

Examples of high-profile bribery and money laundering in the past few years include:

- Uzbekistan telecommunications bribery scheme. Netherlands-based VimpelCom Limited and its Uzbek subsidiary, Unitel LLC, were the subject of enforcement actions in 2016 that sought the forfeiture of more than $850 million in bribe payments to government officials in Uzbekistan. Proceeds of the bribery were laundered through complex transfers into and out of bank accounts in Switzerland and correspondent financial institutions in the United States. VimpelCom and Unitel agreed to pay more than $795 million to resolve global bribery charges. Gulnara Karimova, daughter of the late Uzbek Prime Minister Islam Karimov, was found guilty in 2015 on charges of stealing $1.6 billion in state assets. In 2019, U.S. officials indicted her for accepting and laundering $850 million in bribe payments. In March 2020, she received an additional 13-year prison sentence on additional charges including extortion, racketeering and embezzlement.2,3

- Multinational bribery by a Swedish company. Sweden’s Telefoniaktiebolaget LM Ericsson in late 2019 agreed to pay the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and Department of Justice more than $1 billion to resolve violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and a parallel criminal investigation. U.S. officials charged Ericsson with engaging in a multinational bribery scheme that netted the company hundreds of millions in profits through bribes paid to government officials in China, Djibouti, Indonesia, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Vietnam.4

Sizing Up the Challenges for AML and ABC Programs

The challenges facing anti-money laundering and anti-bribery and corruption programs are as numerous as they are sizable. Many financial institutions, particularly smaller ones, openly worry about the expense of compliance and limited resources, in terms of skilled staff as well as budgets. Nevertheless, they must recognize an immutable fact: the cost to prevent financial crimes is a fraction of the cost to remediate them. In addition to incurring expenses from mandated monitoring programs, the impact of new risk assessments and the imposition of significant fines, financial crimes can impair an organization’s most precious asset: its reputation.

Institutions need to realize what their ABC and AML teams are up against. Financial criminals are a clever and determined lot, motivated by greed and arrogance. They continually seek innovative ways to conceal ill-gotten gains and evade detection. Despite institutions’ best efforts to keep up with rapidly expanding regulatory regimes, statistics on money laundering, bribery and corruption paint a challenging picture for the global financial system. Nowhere does mitigating the growth of financial crime appear easy.

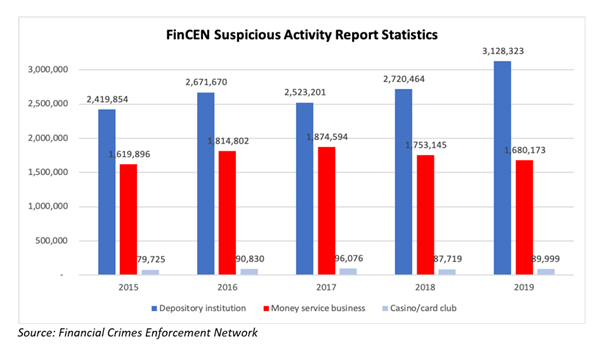

One indicator of a rise in money laundering is the growth in Suspicious Activity Reports tracked by law enforcement authorities. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of SARs filed by depository institutions in the United States increased by 29%, to more than 3.1 million, according to the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.5 SARs filed by money services businesses—such as currency exchanges; businesses that issue, sell, or redeem travelers’ checks, money orders, or stored value cards; and money transmitters—fell in 2018 and 2019 but remain above the number they filed in 2015 (see chart). FinCEN does not publicly disclose the monetary amounts in SAR filings.

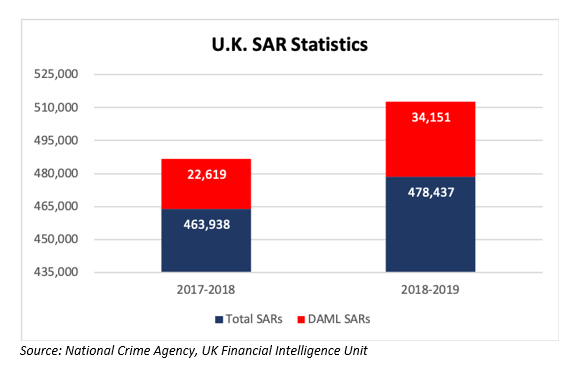

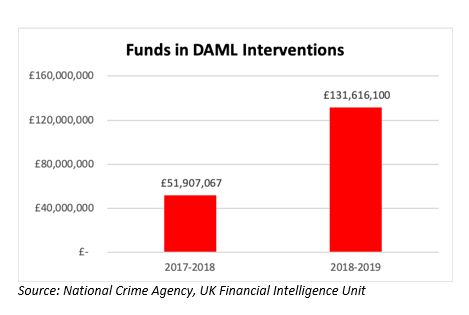

Financial regulators in the United Kingdom have similarly observed similar growth in SARs. According to the National Crime Agency, the U.K. Financial Intelligence Unit in fiscal 2018 processed a record 478,437 suspicious activity reports, a 3% increase from prior fiscal year. In addition, the UKFIU reported 34,151 requests for Defence Against Money Laundering, a more than 52% increase. DAML actions include account freezing orders, cash seizures and other asset recoveries. The amount of funds in DAML requests in fiscal 2018, £131.7 million, more than doubled from the previous year.6

Bribery, corruption and other illicit flows of money carry enormous societal costs. In addition to depriving nations of funds for economic growth, corruption also contributes to political instability, unemployment, poverty and inequity. According to the World Economic Forum, these illicit financial flows cost developing countries more than $1.26 trillion per year. That sum is equivalent to the combined economies of Switzerland, South Africa, and Belgium, and could lift up 1.4 billion people out of poverty and sustain them for at least six years.7

An indicator of the prevalence of bribery is the Corruption Perceptions Index compiled annually by Transparency International. The organization ranks 180 countries on a scale from 100, or “very clean,” to 0, or “highly corrupt.” In its 2019 CPI report, Transparency International noted little progress in curbing corruption worldwide. For example, in the past eight years, 22 countries significantly improved their CPI scores, while 21 saw scores worsen, and the 137 remaining countries had little or no change.8

The countries considered the least corrupt, each with a CPI score of 87, are Denmark and New Zealand. The United Kingdom has a CPI score of 77, ranking it 12th, while the United States ranks 23rd with a CPI score of 69. By comparison, countries targeted for business development, such as the “BRICS,” tend to have lower CPI scores: Brazil’s score of 35 ranks it 106th, Russia is 137th with 28, India and China are tied for 80th with scores of 41, and South Africa is comparatively the least corrupt of the BRICS at 70th with a CPI score of 44.

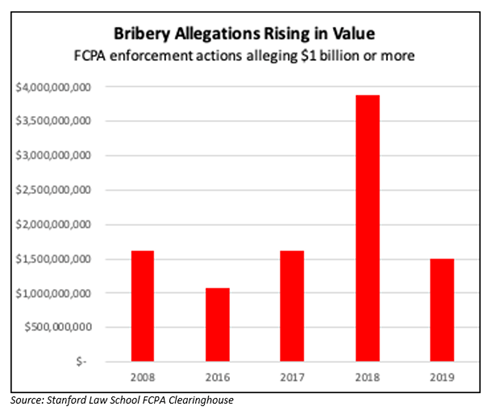

The amount of bribery payments also has increased sharply in the past several years. An analysis by the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Clearinghouse of the Stanford Law School shows that enforcement actions since the FCPA went into effect in 1977 have alleged bribery totaling more than $11.2 billion. The Clearinghouse began analyzing FCPA enforcement actions in 1980. Astonishingly, nearly 72% of that total has come in enforcement action allegations since 2016. Before 2008, FCPA enforcement actions alleging bribery had never exceeded $400 million in any year. In the 12 years between 2008 and 2019, five of those years saw the annual amounts of bribery alleged in enforcement actions exceed $1 billion.9

Because the problem of money laundering, bribery, and corruption is so large, financial institutions are well advised to combat it through a coordinated effort that leverages the strengths of an institution’s compliance resources.

Benefits of Focusing on AML and ABC Compliance Synergies

Anti-money laundering and anti-bribery and corruption efforts focus in different directions, which partially explains why they often are separated within an organization’s operations. For example, AML is primarily about identifying and investigating external threats in transactions. ABC generally involves monitoring threats from internal and potentially third-party sources. It is analogous to a pilot and first officer flying a plane as each looks out a side window. A better way to ensure the plane can safely navigate to its destination is to combine their views into one vantage point and communicate about what each is seeing. Although AML and ABC programs need to retain their distinct specialization to fulfill their respective roles, financial institutions can derive benefits by aligning them.

Advantages to focusing on compliance synergies include:

- Increased effectiveness. When AML and ABC teams collaborate, institutions can make their compliance activities more effective. For example, professionals in each discipline can jointly conduct holistic due diligence on new and existing clients.

- Augmented risk ratings. With some overlapping risk categories, such as high-risk industries and high-risk jurisdictions, ABC and AML can consolidate their resources to develop overall risk ratings. Similarly, ABC risk triggers can augment an institution’s know-your-customer policies, which in turn can open the door to reviews of different types of financial crime risks affecting clients and transactions.

- Comprehensive assessments. Another benefit of aligning ABC and AML teams is they are able to comprehensively assess financial crime risk. This approach can provide unified guidance to financial institutions’ business units, which may, for example, assist units in building client relationships in line with the institution’s risk appetite.

- Greater responsiveness. Institutions that maintain independent AML and ABC resources tend to be reactive in responding to financial crime risks. On the other hand, aligning AML and ABC capabilities enables the institution to respond faster and shift from a reactive response to one of risk anticipation and prevention.

- Enhanced internal fraud detection. Where circumstances necessitate investigation of employees holding accounts at an institution, ABC and AML resources can assist in identifying underlying fraudulent behaviors or abuse of funds that may violate the institution’s policies.

Leveraging AML and ABC resources makes it easier to combat external and internal threats. Certain large financial institutions have constructed compliance teams with integrated departments for financial crime compliance which include AML and ABC, but compliance structures vary. Smaller, resource-constrained institutions may put AML and ABC together for budgetary reasons, yet they may remain separate in other institutions. Alignment of AML and ABC teams creates efficiency and reduces compliance risks, regardless of an institution’s size. In general, a trend among institutions is to group financial crimes risk categories under a single compliance leader.

How to Align AML and ABC

Aligning anti-money laundering and anti-bribery and corruption programs requires a thoughtful approach and support from the highest level of an institution. Key administrative practices that promote successful alignment include:

Tone at the top. Institutions must nurture compliance cultures. Communication about the importance of compliance and collaboration from the top of the organization matters greatly in enhancing cooperation across AML and ABC teams.

Resource allocation. Institutions that succeed in aligning their AML and ABC teams don’t force them to compete for resources and funding. In many institutions, AML often gets the lion’s share of both. When teams have to compete for limited resources, it becomes a zero-sum game: one will win, while the other loses. Financial institutions should strive to avoid unhealthy and counterproductive situations by ensuring teams have the resources they need to perform their roles successfully.

Some institutions have explored collaboration to help with load balancing and deploy resources more efficiently. A surge in requests for investigations or higher-than-normal activity within a certain region can strain an institution’s staff capacity. Consistent global standards and processes across financial crime compliance are desirable for institutions to respond to these situations and avoid duplication of effort. With appropriate tools, operational teams can support AML, sanctions, and ABC compliance. For example, search parameters in onboarding and due diligence on new or existing customers can be expanded to capture relevant data for AML and ABC and escalate findings to the proper subject matter experts within the compliance teams. A holistic set of risk markers also can combine AML and ABC indicators into the institution’s risk rating engine. This approach facilitates analysis at the portfolio and individual customer levels.

Leverage tools. The nature of transaction monitoring in AML has led to the development and adoption of sophisticated tools. Institutions can leverage these to support ABC efforts as well as AML. Examples of such tools are data and analytics, systems that screen the names of politically exposed persons and state-owned enterprises, customization of workflows, tracking and metrics. These can make it easier for institutions to spot suspicious activity and streamline reporting and investigation procedures. Screening for PEP and state-owned enterprises is relevant to AML and ABC teams. Operational teams established for screening alert management can help to support alert disposition for ABC-relevant hits. Therefore, it makes sense to establish shared screening capabilities that benefit both.

Technical tools used for AML and sanctions compliance generally include case management to manage alerts and flag risks. These can be expanded to support ABC programs. Similarly, workflow tools that facilitate data retrieval, data retention, and multiperson use can enhance ABC compliance programs, which typically utilize shared folders, email, and spreadsheet trackers. Workflow tools can be customized for ABC purposes, to capture specific types of information and record decisions and approvals for risks involving gifts and entertainment, third parties, hiring and more.

In addition, advances in data and analytics are enabling institutions to conduct link analysis and machine learning on AML and ABC data. These techniques can uncover relationships and overlaps that are otherwise difficult to spot, further enhancing financial crime compliance.

Consistency in investigations and reporting. ABC teams conducting bribery-related investigations can benefit from partnering with AML financial intelligence units to review historical transactions. FIUs can provide scale, up or down, as circumstances warrant, which can be helpful when ABC teams need to look at more transactional data for suspicious activity.

Implement consistent, continuous training. Between the ongoing evolution of financial crimes and the regulatory requirements designed to contain them, institutions must adopt compliance training programs that provide consistency and continuity, and help employees to understand financial crime risk holistically rather than in parts. It is important that training focus on translating risks that are specific to an institution, how to identify red flags and anomalous behaviors, and establish escalation criteria. It is worth noting that no international standards exist for training in anti-money laundering and anti-bribery and corruption. Seeking expert guidance on how to customize effective training for a specific institution is a good idea.

In many cases, a combination of on-demand training resources and structured learning programs, reflecting the institution’s culture, provides the most effective training to ensure compliance. Unfortunately, too many financial institutions fall into the habit of citing regulations verbatim, rather than training employees in the specific processes needed to apply those requirements. Another consideration for effective training is to consolidate programs where appropriate, so as not to overwhelm employees. For example, KYC and global risk ratings are two areas where AML and ABC professionals have a common need for knowledge.

Test and validate. Organizations that have successfully aligned their teams regularly test and validate the effectiveness of their AML and ABC programs. Institutions must maintain this practice as they adopt new technologies. Ongoing periodic testing of systems is a critical factor in ensuring that an institution’s teams and the tools they rely on for compliance are working properly.

Conclusion

The combined problem of managing money laundering, bribery and corruption risk is daunting for financial institutions of all sizes. AML and ABC professionals play important roles in the effort to prevent and mitigate financial crimes, and going forward there are more effective ways to mitigate risk and benefit from operational efficiencies. It makes sense for institutions to leverage these teams and support them with adequate resources. Aligning AML and ABC programs can deliver a number of benefits, including increased effectiveness in compliance, comprehensive risk assessments and greater responsiveness to the dynamic regulatory environment.

Institutions that are considering leveraging their AML and ABC programs need to be aware that aligning those teams can require adjustments from each of them. Navigating through change is frequently an exercise in managing expectations. For example, if an ABC program largely uses manual processes while the AML team relies on technology, the institution should anticipate it will take time to customize tooling for different purposes and train teams to utilize those resources optimally. Financial institutions should seek answers to the following questions:

- Where in the organizations do the AML and ABC teams currently sit?

If the AML and ABC teams report to different departments, some organizational restructuring may help to align interests. - Does the institution have different risk ratings for customers based on their geography, line of business, and so on?

Differences in risk ratings for similar risk indicators relevant to ABC and AML can signal a need to create a clear set of guidelines and risk appetites when AML and ABC teams closely partner. - Does the institution track anti-bribery and corruption issues raised and the restrictions it implements?

Failure to track issues and restrictions put in place can be risky for institutions from a compliance perspective, besides being a missed opportunity to analyze the effectiveness of their ABC programs. - Are the institution’s ABC processes largely manual or technology-enabled?

Many AML teams use tools and technologies to perform transaction monitoring, alert management, and implement KYC programs and assess risks. ABC teams can benefit from using many of those same tools, but they may require customization and training to use them effectively. - Can the institution consolidate training to reduce staff fatigue?

Attending requisite compliance training sessions can take a toll on staff morale and ability to process new information. Wherever possible, financial institutions should look to consolidate required training to keep staff up to date and eager to ensure compliance.

The stakes in anti-money laundering and anti-bribery and corruption have never been higher. Institutions can strengthen their compliance programs by aligning their AML and ABC teams. To do so, they should take deliberate and thoughtful steps to give their AML and ABC teams the best opportunity to succeed.

1 Transparency International, “25 Corruption Scandals that Shook the World,” 21 August 2019; https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/25_corruption_scandals#Azerbaijani%20Laundromat

2 U.S. Department of Justice, “VimpelCom Limited and United LLC Enter into Global Foreign Bribery Resolution of More than $795 Million,” 18 February 2016; https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/vimpelcom-limited-and-unitel-llc-enter-global-foreign-bribery-resolution-more-795-million

3 “Former Uzbekistan Leader’s Daughter Found Guilty of Graft,” Financial Times, 18 March 2020; https://www.ft.com/content/75e5335c-6906-11ea-800d-da70cff6e4d3

4 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, “SEC Charges Multinational Telecommunications Company With FCPA Violations,” 6 December 2019; https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2019-254

5 Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, “Suspicious Activity Report Statistics,” 2015-2019; https://www.fincen.gov/reports/sar-stats

6 National Crime Agency, UK Financial Intelligence Unit, “Suspicious Activity Reports Annual Report 2019”; https://nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/who-we-are/publications/390-sars-annual-report-2019/file

7 World Economic Forum, “Corruption Costs Developing Countries $1.26 Trillion Every Year—Yet Half of EMEA Think It’s Acceptable,” 9 December 2019; https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/corruption-global-problem-statistics-cost/

8 Transparency International, “Corruption Perceptions Index 2019”; https://www.transparency.org/cpi2019

9 Stanford Law School Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Clearinghouse, “Total Bribery Alleged in FCPA-Related Enforcement Actions”; http://fcpa.stanford.edu/statistics-analytics.html?tab=5