In the most consequential update to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) since the 2001 passage of the USA PATRIOT Act, the U.S. Congress on 11 December passed a wide-ranging bill that broadens and updates the BSA and the U.S. anti-money laundering/combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regime, creates a national beneficial ownership reporting framework for legal persons, and fosters innovation and information-sharing.1 The Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AML Act) and its inclusion in the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) demonstrate strong bipartisan consensus in Congress. The NDAA passed both houses of Congress by wide margins, and is likely to withstand a potential veto.2 If it becomes law, the AML Act will launch a rulemaking and policy development process that is likely to extend over several years and will require sustained focus by the public and private sectors.

- The bill makes important revisions and amendments to the BSA that update its scope and coverage to make the law both more flexible and wider-reaching. These include expanding the purpose of the BSA to emphasize preventive measures to protect the U.S. financial system and national security;3 bringing antiquities dealers into its purview;4 and ensuring that virtual asset service providers (VASPs) are fully covered.5

- The bill requires certain companies incorporated in or operating in the United States to report their beneficial owners—the individuals who ultimately own and control them—to the U.S. financial intelligence unit, the Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).6 Currently, individuals seeking to incorporate companies in U.S. states, as in many foreign jurisdictions, can conceal their identities, and illicit actors have taken advantage of opaque corporate forms to engage in illicit activity.7

- The bill promotes a more unified and prevention-focused national AML/CFT approach by requiring the Department of the Treasury—in consultation with the Attorney General, relevant federal regulators, and the national security agencies—to identify and maintain national AML/CFT priorities.8 The bill also requires financial institution (FI) examiners to attend annual AML/CFT training9 and establishes personnel rotation and secondment programs for AML/CFT experts in government.10

- The bill also promotes information sharing between the public and private sectors to foster a common understanding of illicit finance threats and risks and of FIs’ responsibilities. It requires examiners to assess the extent to which FIs have incorporated the national AML/CFT priorities into their risk-based AML/CFT programs.11 The bill also re-establishes FinCEN Exchange, a public-private information-sharing partnership, as a statutorily mandated body with the purpose of protecting the financial system and promoting national security.12

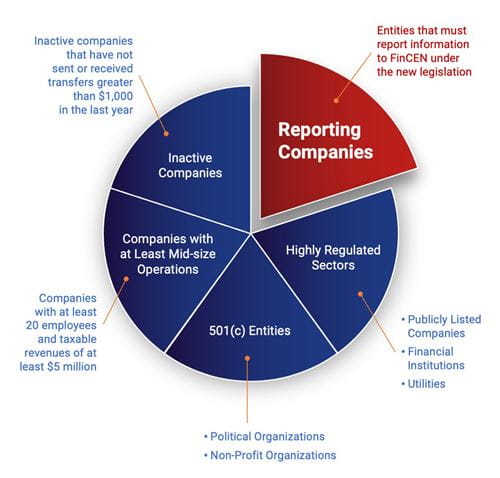

The bill’s most immediately consequential element is the introduction of a beneficial ownership reporting requirement for many companies, which brings the United States closer to compliance with a global movement to end or limit corporate secrecy. Companies incorporated in, or authorized to do business in, the United States will be required to report their beneficial owners to FinCEN, with some exemptions, as shown in Figure 1. Following implementation of this requirement, the United States will no longer rely on FIs as the primary actors responsible for the collection and maintenance of beneficial ownership information for all U.S. companies. FIs will have access to the data FinCEN collects, but the exact nature of this access remains unclear.

- Companies that qualify as reporting entities will be required to report their beneficial owners—defined as any individual exercising substantial control over the entity or owning or controlling at least 25 percent of the company’s ownership interests—to FinCEN at the time of registration, or, for companies that are already registered, within two years of passage of the AML Act.13,14 Certain categories of companies, such as highly regulated institutions—including FIs and utilities—nonprofit organizations, inactive companies, and companies with at least 20 employees and $5 million in revenue are exempt from the reporting requirement (see Figure 1).15

- FIs will have access to the FinCEN beneficial ownership database to support their customer due diligence (CDD) efforts, although only with the consent of the reporting entity whose information they are seeking.16 Currently, under a regulation known as the CDD Rule, FIs are required to identify the beneficial owners of their customers. They are permitted to rely on their customers’ certifications of who qualifies as a beneficial owner, but are required to verify the identity of any individuals identified by their customers.17

- The bill directs the Department of the Treasury to revise the CDD Rule to reflect the introduction of the database and the revised rule is likely to set the parameters for FI access to the database18 and to determine when FIs are permitted or expected to replace or verify their customers’ certifications with the information in the database. Because the definitions and exemptions in the AML Act do not overlap completely with those in the CDD Rule, FIs will continue to have obligations to collect information not included in the FinCEN database.

| Implications for Antiquities Dealers and the Art Market

The AML Act of 2020 adds dealers in antiquities to the list of entities that are subject to the BSA19 and calls on the Treasury Department to conduct a study of money laundering in the broader art market and to make a recommendation about whether increased regulation of the sector would prove helpful to law enforcement.20 Although the exact requirements for participants in the antiquities sector will be determined by regulations that will be drafted within a year of the enactment of the Act, antiquities dealers will generally be required to have AML/CFT programs, to identify their customers, and to report suspicious transactions to FinCEN. They also will be subject to FinCEN’s monitoring for compliance with these requirements. The move comes after years of concern that terrorists can abuse the antiquities market to raise funds.21 The Islamic State terrorist group is known to have plundered archaeological sites in the areas under its control, and looted antiquities from Iraq and Syria have been openly sold on the internet.22 |

The bill also expands the BSA’s goals and reach, encourages innovation and information-sharing, and bolsters the capacity of and tools available to U.S. agencies responsible for administering and enforcing AML/CFT rules. These reforms underscore Congress’s recognition that the current regime needs to adapt to changing conditions and to innovations in AML/CFT to better prevent, detect, and combat illicit finance and the abuse of the U.S. financial system.

- The bill provides new tools to law enforcement, most notably by allowing the Departments of Justice and the Treasury to subpoena any foreign bank that maintains a correspondent account in the United States and request any records relating to accounts at that bank, even if maintained outside of the United States.23 It also expands the BSA whistleblower program to further encourage reporting of BSA violations24 and makes it a criminal offense to conceal or misrepresent a politically exposed person’s interest in a transaction.25

- The bill seeks to ensure that the U.S. AML/CFT regime remains responsive to innovation and technological developments in the financial sector by explicitly encouraging technological innovation for AML/CFT purposes, requiring FinCEN and federal functional regulators to appoint “innovation officers” to reach out to FIs and other stakeholders with respect to new methods and technologies that may assist in compliance,26 and ensuring that VASPs are brought under the purview of the BSA.27, 28

- The bill promotes communication and information sharing between FinCEN and FIs and also between U.S. FIs and their foreign branches and affiliates. It establishes a pilot program in which covered FIs will be able to share information related to suspicious activity reports within their respective financial groups.29 Additionally, it requires FinCEN to provide regular analysis to FIs on illicit finance typologies and threat patterns and trends, and to appoint new domestic liaisons and foreign attachés to engage with the private sector.30 The bill also establishes or codifies a host of initiatives, such as FinCEN Exchange, that provide opportunities for private sector engagement.31

FIs should be aware that the bill brings immediate changes to relevant legal authorities—including increased penalties for noncompliance—and also sets the stage for potential new regulations over the next several years by requiring government agencies to study and submit reports on a variety of topics. As FIs work to come into compliance with new requirements, they should also engage with supervisors and regulators regarding possible future regulation and reform. They may also consider opportunities to participate in newly created or continuing for the private sector to provide input on the further development of the U.S. AML/CFT regime.

- In case of repeat violations of the BSA, the bill allows for civil penalties that are double the maximum for a first violation, or three times the violator’s profit resulting from the violation.32 It also requires the repayment of profits and bonuses by those individuals convicted of BSA violations, and bars individuals found to have committed an egregious violation of the BSA from serving on the board of directors of a U.S. FI for ten years following the date of conviction.33

- Congress further requires a report from the Department of Justice regarding its use of deferred prosecution agreements and non-prosecution agreements to address BSA violations, including the extent to which Justice is coordinating with the Department of the Treasury and federal and state regulators when entering into, changing, or terminating such agreements.34

- Additional changes to reporting requirements for FIs may follow from, for instance, the bill’s requirement that the Comptroller General study and report on the effectiveness of the currency transaction reporting regime already in effect. The Comptroller must commence the study no later than January 2025.35

- A separate, Russia-focused section of the NDAA requires the Treasury Department to identify, within one year, any additional regulations or requirements needed to combat money laundering. That section requires consideration of a new national register to track ownership of real estate as well as new reporting and customer due diligence requirements for the real estate sector, law firms, and other trust and corporate service providers.36

Endnotes

1 The AML Act of 2020 is Division F of the William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 [2021 NDAA], https://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20201207/CRPT-116hrpt617.pdf.

2 Andrea Shalal, “Trump Revives Threat to Veto Defense Bill, Teeing up Battle with Lawmakers,” Reuters, December 13, 2020, at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-defense-trump-idUSKBN28N0O5; Bryan Bender, “Biden Lobbied to Rejoin Iran Deal,” Politico, December 14, 2020, at https://www.politico.com/newsletters/morning-defense/2020/12/14/biden-lobbied-to-rejoin-iran-deal-792251.

3 2021 NDAA, Section 6101.

4 2021 NDAA, Section 6110.

5 2021 NDAA, Section 6102.

6 Title LXIV, Establishing Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting Requirements, of the 2021 NDAA.

7 Chip Poncy, “Beneficial Ownership: Fighting Illicit International Financial Networks Through Transparency,” Testimony before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, February 6, 2018, at https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Poncy%20Testimony.pdf.

8 2021 NDAA, Section 6101, pp. 2805-6.

9 2021 NDAA, Section 6307.

10 2021 NDAA, Section 6104, 6106.

11 2021 NDAA, Section 6101.

12 2021 NDAA, Section 6103.

13 2021 NDAA, Section 6103, p. 2956.

14 2021 NDAA, Section 6103, pp. 2969-70.

15 2021 NDAA, Section 6103, pp. 2959-68.

16 2021 NDAA, Section 6103, p. 2982.

17 31 CFR § 1010.230.

18 2021 NDAA, Section 6103, p. 3007.

19 2021 NDAA, Section 6110.

20 2021 NDAA, Section 6110(c).

21 U.S. House Committee on Financial Services, “Preventing Cultural Genocide: Countering the Plunder and Sale of Priceless Cultural Antiquities by ISIS,” April 19, 2016, at Hearing entitled “Preventing Cultural Genocide: Countering the Plunder and Sale of Priceless Cultural Antiquities by ISIS” | Financial Services Committee (archive.org); Matthew Sargent et al., Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open Source Data, Rand Corporation, 2020, at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2706.html; Brooks Tigner, “Europe Moves to Curb ISIS Antiquity Trafficking,” Atlantic Council, September 13, 2019, at https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/europe-moves-to-curb-isis-antiquity-trafficking/.

22 Steve Swann, “Antiquities Looted in Syria and Iraq Are Sold on Facebook,” BBC, May 2, 2019, at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-47628369.

23 2021 NDAA, Section 6308.

24 2021 NDAA, Section 6314.

25 2021 NDAA, Section 6313.

26 2021 NDAA, Section 6208.

27 Although FinCEN has maintained since at least 2013 that VASPs are covered by the BSA, this claim has faced legal challenge. The revisions to the BSA ensuring that the definition of “money transmitting businesses” applies to transmitters not only of “funds” but also of virtual assets should place FinCEN’s supervision of these entities on a firmer legal basis. See our recent policy alert on similar attempts at more firmly grounding FinCEN’s supervision of VASPs.

28 2021 NDAA, Section 6102.

29 2021 NDAA, Section 6212.

30 2021 NDAA, Sections 6106, 6107, and 6206.

31 2021 NDAA, Section 6103.

32 2021 NDAA, Section 6309.

33 2021 NDAA, Sections 6312 and 6310.

34 2021 NDAA, Section 6311.

35 2021 NDAA, Section 6504.

36 2021 NDAA, Section 9714.